Original Research

Stakeholder Perception of Extracurricular Activities at the Tertiary Level in Vietnam

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

The statement of NCES on its website that "extracurricular activities (ECAs) provide a channel for reinforcing the lessons learned in the classroom, offering students the opportunity to apply academic skills in a real-world context, and are thus considered part of a well-rounded education" has further consolidated the significance of this component in a school's curriculum development. No matter how important these activities are, they have seemingly not received due attention and investment from universities in Vietnam. This study was conducted at four universities in Vietnam to examine the perceptions of three stakeholders, namely administrators, teachers, and students about ECAs. Survey questionnaires and informal interviews were used for data collection. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse quantitative data while qualitative data were approached by deductive content analysis. Major findings reveal both matches and mismatches in the perceptions of the participants, and there was an association between the encouragement of extracurricular activities and students' engagement as well as improvement in their academic performance; however, an unwelcome fact remained regarding students' participation rate, teachers’ belief, and administrators' engagement.

Stakeholder Perception of Extracurricular Activities at the Tertiary Level in Vietnam

Tran Thi Ngoc Lien

Haiphong University of Management and Technology, Vietnam

ABSTRACT The statement of NCES on its website that "extracurricular activities (ECAs) provide a channel for reinforcing the lessons learned in the classroom, offering students the opportunity to apply academic skills in a real-world context, and are thus considered part of a well-rounded education" has further consolidated the significance of this component in a school's curriculum development. No matter how important these activities are, they have seemingly not received due attention and investment from universities in Vietnam. This study was conducted at four universities in Vietnam to examine the perceptions of three stakeholders, namely administrators, teachers, and students about ECAs. Survey questionnaires and informal interviews were used for data collection. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse quantitative data while qualitative data were approached by deductive content analysis. Major findings reveal both matches and mismatches in the perceptions of the participants, and there was an association between the encouragement of extracurricular activities and students' engagement as well as improvement in their academic performance; however, an unwelcome fact remained regarding students' participation rate, teachers’ belief, and administrators' engagement. |

| Keywords: Extracurricular Activities, Perception, Stakeholders, Tertiary Level |

Introduction

Extracurricular Activities (ECAs) have long been considered an essential part of a well-rounded education as they have been proven to support students in various aspects from the very basic ones such as boosting their self-esteem, expanding their interests, and enhancing their learning engagement to more general targets including improving their self-efficacy, advancing their academic performance, and increasing their employability.

In recent years, educational researchers have emphasized the critical role of organizing ECAs to promote an effective school environment, which in return helps to secure the success and development of a school, especially in increasing learner enrolment and retention. Thanks to ECAs, school programs can be made more interesting (Borman & Spring, 1995), school culture can be developed (McNeal, 1999), and school curriculum can be further enriched (Piirto, 2011). Additionally, students can greatly benefit from this policy as they are able to get involved in “real-life creative problem-solving scenarios” (Piirto, 2011), enhance their "creativity, productivity and well-being" (Olibie & Ifeoma, 2015, p. 4850), increase their general life satisfaction and improved their level of academic achievement (Toyokawa & Toyokawa, 2002; Wilson, 2009), and better overall personal development (Jane et al., 2016). The 2019 World Bank report acknowledged the importance of ECAs to empower the young generation to pursue 21st-century skills.

In Vietnam, the Ministry of Education issued Decision No.72 on 23 December 2008, regulating the organization of extra-curriculum activities at all school levels, and this action indicates the involvement of an administrative body in this field. A great deal of attention has been paid to ECAs by different universities nationwide, notably from the prestigious ones such as Foreign Trade University, Fulbright University Vietnam, and Vietnam National University. However, an official evaluation of the impact of ECAs on students and their institutions has not yet been conducted and published. In a bid to have a better insight into the effects of ECAs, the researcher carried out this study to figure out ECA perceptions of three key stakeholders, namely students, teachers, and university administrators of four universities in the north of Vietnam, and make possible recommendations to improve this practice.

Literature review

Extra-curricular activities: what and why?

Extracurricular activities are programs outside of the regular school curriculum. In other words, they are referred to as "life outside the classroom". These activities may include such fields as athletics, community service, employment, arts, hobbies, and academic and nonacademic clubs. They serve an important function of "supplementing the regular school curriculum" (Asmal, 2000, p. 10) and, therefore, take the form of special interest groups that attract voluntary followers and do not require formal assessments. Sullivan (2018, p. 16) suggested three main themes involving ECAs, namely "diverse range of activities, separate to the formal curriculum, and a context for developing skills" while Thompson et al. (2013) and Greenbank (2015) went further at length, referring ECAs to specific activities including part-time employment, volunteering, participation in sporting and cultural activities, and work placements.

Rationales behind the employment of extracurricular activities may vary due to the school's overall concern or differences in level of education. The main one, however, appears to be universal: that is for both the academic and personal development of the students. In the US, Fredricks and Eccles (2006a, 2006b) and Shulruf (2010) found a correlation between ECAs and adolescents' academic achievement and educational attainment. In the UK, Greenbank (2015) and Thompson et al. (2013) shared the same findings and went further discussing the link between ECAs and students' well-being. While Umeh et al. (2020) and Iddrisu et al. (2023) associated ECAs with the ability to deter antisocial behavior among students at higher levels of education, Vinas-Forcade et al. (2019) concluded that ECAs' participation could lower the dropout rates as it brought about academic achievements.

Extra-curricular activities and student development

Academic performance

The relationship between ECAs and students' academic performance has long been a source of constant debate and has attracted the interest of a plethora of researchers, school administrators, teachers, and students. A wealth of studies have been conducted to find out the answer to the question as to whether ECA involvement can better students' academia; however, most of them were carried out at lower education but not at the tertiary level. Research findings did not satisfy all the stakeholders as ECA participation exerted both positive and negative impacts on student performance at school.

Annu and Sunita (2014) did research in India about the implementation of ECAs at a secondary school and found that students who participate in these extracurricular activities generally benefited from many opportunities available to them. They did have better grades, higher standardized test scores, and higher educational attainment. The absenteeism rate was lower, while self-efficacy was higher. Through her study in the UK, Sullivan (2018) posited the improvement in students' academic abilities via a school leader's report about students' stronger GCSE performance and a parent who admitted that her child did better at school after participating in a creative writing club.

There have been common beliefs among other researchers that ECA involvement exerted a certain impact on students' academic achievements due to the increased relatedness with the school (Cosden et al., 2004), the social connections that the students could build with their peers, their mentors, and with the outside school community (Toomey & Russell, 2013), and the skills and knowledge that they attained during their participation (Snellman, Silva, & Putnam, 2015). Sharing the same viewpoint, Yousry (2022) concluded that "ECAs support the enhancement of students' cognitive skills, which are integral to the development process of students' academic excellence" (p. 75). This positive result could be attributed to the sense of motivation developed among ECA participants and the stronger engagement in learning they got while performing these activities. For adolescents, the association between ECAs and academic improvements has also been consolidated. Camp (1990) reported the indirect impact of extracurricular participation on improving academic performance. Mahoney and Cairns (1997) showed evidence for the involvement in school extracurricular activities in lowering dropout rates and easing antisocial behaviors. At the tertiary level, Buckley and Lee (2012) talked about the increased degree of tension that university students had to suffer when participating in ECAs. Diniaty and Kurniati (2014) went so far as to suggest the negative correlation between ECA involvement and academic performance though they admitted that extra-curricular activities were "very influential to the distribution of talent, personal interests and abilities of students" (p. 12). These researchers said the more students were engaged in ECAs, the poorer their academic ability was. Leung, Raymond Ng, and Chan (2011) reported the same findings that ECA involvement could not enhance the learning effectiveness of students in a research conducted at a university in Hong Kong.

Skills development

Though ECAs take the form of voluntary interest groups, they are bound to help students improve a wide range of skills necessary for their rounded development and their future careers. The first one is the ability to work in a team because students need to collaborate to fulfill a set duty, for example, helping old and childless people in the community or preparing for a school concert. Buckley and Lee (2021) agreed that in addition to the improvements in "a range of problem-solving skills including project management, budgeting, and team management" (p. 42), advances were observed in teamwork skills when the participants joined a team which "works together in o to create and run a society which people can connect and engage with" (p. 42). They collaborate toward the fulfillment of a common goal, and for this to be realized, they are supposed to know how to settle a conflict or deal with an argument. Gradually, the active group members can sharpen their problem-solving ability and communication skills. By partaking in a variety of ECAs, which provide them with chances to experience real-life situations, the students can acquire the basic skills needed in everyday life such as "problem-solving, analytical, and critical thinking skills" (Lyoba & Mwila, 2022, p. 5).

Besides the aforementioned set of skills, active members of ECAs could attain other social skills such as conflict settlement, leadership, and time management (Annu & Sunita, 2014; Sullivan, 2018). This is because ECAs allow students to practice, show their interests, and freely immerse themselves in real-life situations. The participants also need to try their best to clear off all the possible obstacles and find the best way to fulfill their goals. Motivation and engagement are the true driving forces for people to be the better versions of themselves.

Student self-efficacy

Self-efficacy has been proven to be significant in a student’s learning process because it affects learner motivation and knowledge acquisition. This concept is known as a person's belief in their ability to fulfill a task or achieve a goal, and it entails a person's faith in themselves to "control their behavior, exert an influence over their environment, and stay motivated in the pursuit of their goal" Cherry (2023, p.1). Its impacts on student performance both academically and non-academically have been widely acknowledged in education studies in general and socio-cognitive linguistics in particular (Bandura, 1997; Griffin & Griffin, 1998; Pajares & Urdan, 2006), and such influences may vary in duration (Lee & Vondracek, 2014).

Bandura (1997) defined self-efficacy as the 'beliefs in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments' (p. 3), and according to him, this ability could be extended to the capability to partake in communal tasks to sustain relationships within their social circle (social self-efficacy), the ability to self-manage their behavior (self-regulatory efficacy), the capacity to engage in professional development (career self-efficacy), and the ability to manage one's learning activities (academic self-efficacy). The main reason behind the impact of learner self-efficacy is down to the attempt to set goals for students themselves and use appropriate learning strategies to reach their full potential (Bandura, 1989, 1991; Zimmerman et al., 1992).

Pedagogic strategies have been used to promote students’ belief in themselves, and one of them is to encourage active involvement in ECAs. Doing what the learners are capable of and engrossed in helps improve their self-esteem and self-confidence. The availability of numerous individualized and group activities enables students to up their mood, raise their self-belief, and attain success. It is admitted that success boosts a learner's belief while failure spoils it. A positive mood fuels their self-confidence, while stress and anxiety can sabotage it (Bandura, 1989, 1991a; Margolis & McCabe, 2006).

Griffiths et al. (2021) came up with three main conclusions in their study at a university. First, they posited an integral association between engagement with ECAs and self-efficacy, claiming that the more ECAs students were involved in, the more their self-efficacy could be promoted. This means the participants of more than one ECA developed “higher self-efficacy specific to the university context than those partaking in one ECA only or none” (p1305). Second, there is a relationship between types of ECAs and degree of self-efficacy because they found out that ECAs which are "more closely associated with the HEI environment (student representative activities) were linked with higher self-efficacy scores overall than off-campus activities (volunteering and part-time work)" (p.1305). Thirdly, the research results "do not support a causal effect between engagement with ECAs and higher self-efficacy at university over time” (p. 1305) as the research findings indicated that all respondents, regardless of ECA engagement, raised their overall self-efficacy over time.

Similar to Griffiths et al. (2021), Huang and Chang (2004), Stephens and Schaben (2002), and Hunt (2005) proposed that ECA involvement went hand in hand with academic achievement and improvements in the overall competence of students through the teamwork they got involved in. Similarly, Fung et al. (2007) showed a positive correlation between ECA participation and self-efficacy, while Bekomson et al. (2020) went further as to various types of self-efficacy that are affected by students' involvement in ECAs, including social self-efficacy, academic self-efficacy, language self-efficacy, moral self-efficacy and overall self-efficacy (p. 85). Contrary to the positive impacts of ECAs on students' academia and self-efficacy, Leung, Raymond Ng & Chan (2011), who asserted that ECAs could not support the academic ability of students, assumed that engagement in these off-campus activities may not have any influence on self-efficacy, since the poor performance of students at school may prevent them from developing their self-confidence.

Student engagement

Viewed as a multidimensional concept, student engagement is commonly known for three main types namely behavioral, emotional, and cognitive (Fredricks et al., 2004). The first one refers to students' academic involvement and participation in learning activities. It includes effort, persistence, attention, a sense of discipline, etc. The second type involves the affective attitudes, which can be either the positive or negative reactions that the students have towards their school, classroom, classmates, and teachers. It may be the feelings of boredom, happiness, sadness, or anxiety, the sense of belonging, and the like or dislike attitudes toward school. The last is viewed as students' willingness to master uphill skills. This type goes further beyond the behavioral and emotional, adding some features such as self-regulation, a “preference for challenge…and hard work” (p63-64), efforts in mastering new knowledge and skills, and usage of learning strategies.

Engagement plays a crucial role in promoting student learning; the more committed the students are toward their learning process, the more likely they will excel academically. Astin (1984) confirmed a positive correlation between student's engagement at university and the amount of knowledge and the level of personal development they gain. Productive involvement brings about positive learning attitudes, a sense of connectedness, active learning, strong commitments, and devotion, more time on task, and eventually academic achievement (Astin, 1984; Braxton Milem, & Sullivan, 2000; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2006; Pike, 2006). Not only the students but also their institutes can reap benefits from this. Low dropout rates (Fredricks et al., 2004), for example, helps a university to earn a reputation and income. Moreover, colleges and universities that can engage students more in ECAs are rated higher in terms of quality than those where students are less engaged (Kuh, 2001). ECA participation increases students' affiliation with their institution, leading to better learning experiences and academic outcomes (Munir & Zaheer, 2021).

To increase student engagement, several strategies can be employed, ranging from satisfying individual needs such as providing students with free choices in learning, privatizing learning materials, and giving timely feedback to bettering the learning environment and policies. Among the popular choices is the encouragement of students to get involved in ECAs. A study conducted in Cairo, Egypt, by Yousry (2022) concluded that ECAs could increase school engagement and reduce dropout rates. He said an ECA-based academic curriculum worked well to foster both students' academia and support to nurture their interests or talents. This finding was similar to what Craft (2012) concluded, that is, students' participation in ECAs played a key role in lowering the dropout rates. Lamborn et al. (1992) and Finn (1993) were in line with Yousry (2022), suggesting that students' participation in ECAs increased their sense of engagement or attachment to their school, thereby decreasing the likelihood of school failure and dropping out. Doing research in an open and distance learning setting (ODL), Munir and Zaheer (2021) admitted that despite the great challenge of applying ECAs in a distance learning institute, student participation in ECAs positively affects the overall student engagement with the university and ECAs has become a good source for peer and teacher-student interactions. The fact that students' sense of belonging increased contributed to their better performance, which is important and meaningful for ODL. These researchers also suggested the application of ECAs for any institution that wants to increase student engagement. These activities help to raise student engagement, self-confidence, employability skills, and motivation, which is the educational institution's ultimate objective. Much as they are, research about the relationship between ECAs and student engagement has been mainly conducted at the lower level of education. The availability of these studies in a university context is still insufficient.

Employability

Employability refers to a person's capability for attaining and maintaining employment. As entry into the labor market is no longer a piece of cake, graduates have to make great efforts to give themselves a cutting edge over others. In addition to adequate knowledge and excellent disciplinary skills, the pre-requisite for recruitment, job seekers are expected to show a range of complementary competencies and skills to be more competitive (Clark et al., 2015). Facts indicate that employers tend to seek and welcome those who have the know-how in the job they offer and those who can handle things in real-world situations rather than the people who just mastered the theory or "demonstrate their academic capability as printed on the university transcript" (Hui et al., 2021). In other words, employers care more about the graduates' ability to deal with real-world challenges than their pure academic performances (Haste, 2001; Kalantzis & Cope, 2012).

There are many Approaches for enhancing employability skills among new graduates, and taking part in ECAs is one of the available options for HE students. Studies have shown that ECAs are conducive to the development of employability skills among undergraduate students (Greenbank, 2015; Thompson et al., 2013). Involvement in ECAs allows the would-be graduates to immerse in real-life situations, apply theoretical knowledge in practice, and sharpen their professional skills. Keenan (2010) said that ECAs exerted positive impacts on labor market outcomes and career success because participation in these activities inaugurated positive academic outcomes and put to good use the skills required in the workplace. The competencies required of a potential candidate can be developed through his participation in extracurricular activities (Boyatzis, 2008; Clark et al., 2015). Active engagement in ECAs is closely associated with better leadership and interpersonal skills (Shaffer, 2019), a higher success rate in job hunting (Chia, 2005), and a bigger potential to be appointed to a senior position (Bartkus et al., 2012).

Stakeholders at a tertiary institution

Freeman (1984) recognized a stakeholder as any individual or group of individuals who affect the existence and development of a company or being affected by it. Similarly, Bryson (2004) identifies stakeholders as individuals or groups that have the power to directly impact the future of the organization. In education, stakeholders are those demonstrating their interest in the system and those who directly participate in it or who it can affect.

Defining the stakeholders in higher education plays a key role in not only establishing the competitive edge for each institution but also in identifying the needs and setting up the means to meet them. Stakeholders have their roles to play and influence the existence of their institution, so the management board must be responsible for defining who they are, what roles they play in the system, and what their real needs are (Lam & Pang, 2003).

Mitchell et al. (1997), the father of Stakeholder Salience theory, classified a university's stakeholders in terms of power, legitimacy, and urgency. In this way, the stakeholders of a university fall within three groups: Latent stakeholders hold only one of the three attributes; Expectant stakeholders possess two of the three attributes; and Definitive stakeholders own all three attributes. The identification and classification of university stakeholders became easier when it comes to the roles they take and their influence over the operation and existence of an institution. From this perspective, Matkovic et al. (2014) suggested two types of stakeholders: the internal and the external ones.

Table 1. University stakeholders. Matkovic et al. (2014, p. 2273)

| External stakeholders | Internal stakeholders |

• State government, • Former and potential students, • Students parents, • Business partners, • Employers, • Employment agencies, • Suppliers (alumni, high schools, service providers, other universities, ...), • Competitors (direct, potential, substitutes), • Donors, • Communities, • Government and non-governmental regulators, • Intermediaries (banks, funds, professional associations, chamber of commerce, business clusters, science and technology parks, business networks, ...), • Joint venture partners. | • Governing board, • Current students, • Management (rector, dean, senior administrators), • Employees (teaching and research staff, administrative staff, support staff). |

In this study, we surveyed three groups of stakeholders. First, school administrators are those who constantly get involved in the process of managing the school, making decisions on curriculum development, and keeping an eye on the employment of ECAs. Second, teachers are directly in charge of student education and take control over what they teach and how they instruct their classes. They prepare lessons based on the assigned curriculum and care for every progress or failure of the students. These stakeholders are required to be flexible with teaching methods and approaches and ready to adapt to novelty in education. They are also expected to make recommendations for better changes in curricula and be fully responsible for the application of ECAs. Teachers are instrumental in the success of a school because they help improve student performance, minimize the dropout rate, and guarantee job security and income. Third, students are the primary stakeholders. Any policies, changes, and offerings are for them and directly affect them. The application of ECAs is also to satisfy their needs and for their betterment.

Methodology

Research question

To fulfill the research aim and objectives, the researcher attempted to answer the research question that follows: “What are the perceptions of students, teachers, and administrators on the impact of ECAs in some universities in Vietnam?”

A survey research

Nunan (1991) proposed that a survey is "widely used for collecting data in most areas of social inquiry, from politics to sociology, from education to linguistics" (p. 40). Kasunic (2005, p. 3) stated that a survey enables the researchers to "generalize about the beliefs and opinions of many people by studying a subset of them." Leedy and Ormrod (2005) said that survey research is employed to gather information about population groups to learn “their characteristics, opinions, attitudes, or previous experiences” (p.159). The method applied in this study is an exploratory survey as this type is very flexible, cost-effective, and open-ended. It does not require any fixed models or prior studies and allows great flexibility and adaptability (Cohen & Manion, 1985). The goal of exploratory research is to explain why or how a previously studied phenomenon takes place, and it is really helpful in narrowing down a challenging or nebulous problem that has not been previously studied. Also, its preliminary results can lay the groundwork for future analysis. This research made use of Kasunic's model and its procedure for simplicity and specification.

A set of two questionnaires was utilized. Questionnaire one, which consists of two parts with 52 statements, was used to seek the perceptions of both students and teachers on the application of ECAs and how participation in these activities impacts their academic performance, skills, self-efficacy, engagement, and employability. Questionnaire two, with 20 statements, aimed to examine the university administrators' perception of ECAs: how challenging it was to organize these activities and how the employment of ECAs affected their institutions. The Likert scale was used to measure the level of assessment on different aspects mentioned.

Table 2. Students and teachers’ perceptions of ECAs – questionnaire one

Part A: Put a tick (v) in the selected box | ||

| ECAs and the learning program | Level of ECA participation | |

1. strongly related | 1. highly active | |

2. related | 2. active | |

3. somewhat related | 3. somewhat active | |

4. not related at all | 4. not active | |

5. don’t know | 5. no participation at all | |

| ECA SIGNIFICANCE | ||

1. very much | ||

2. much | ||

3. normal | ||

4. little | ||

5. very little | ||

Part B: Put a tick (v) in the selected box. Please keep in mind that 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3= neutral; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree. | ||

| ECA participation in allows me/my students to: | ||

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE | 1. develop the science and theory learned | |

| 2. support academically and understand the learning materials | ||

| 3. increase GPA | ||

| 4. raise exam scores | ||

| 5. stay focused on learning | ||

| 6. be inspired to learn | ||

| 7. seek support from peers in learning | ||

| 8. discuss learning problems with peers and teachers | ||

SKILLS DEVELOPMENT | 9. deal with uprising problems easily | |

| 10. collaborate with people sensibly | ||

| 11. communicate with different people | ||

| 12. settle a conflict | ||

| 13. start an argument | ||

| 14. involve in leadership training | ||

| 15. manage time effectively | ||

| 16. improve social skills | ||

| 17. better personal organization | ||

| 18. nurture critical thinking skills | ||

STUDENT ENGAGMENT | 19. promote a sense of discipline and conformance to institutional norms and expectations | |

| 20. promote student self-regulation, | ||

| 21. promote peer interaction | ||

| 22. promote student-teacher interaction | ||

| 23. promote solidarity with friends | ||

| 24. promote a sense of belonging and connectedness to the institution | ||

| 25. spend more effort, persistence, attention on learning | ||

| 26. increase liking toward school. | ||

| 27. increase willingness to master uphill skills. | ||

| 28. show preference for challenges and hard work, | ||

STUDENT SELF-EFFICACY | 29. control behavior | |

| 30. do communal tasks | ||

| 31. engage in professional development | ||

| 32. manage one’s learning activities | ||

| 33. improve self-esteem and raise self-confidence | ||

| 34. stay motivated in the pursuit of academic goals | ||

| 35. keep inner balance and well-being. | ||

| 36. up mood | ||

| 37. increase resilience | ||

| 38. improve physical and mental health | ||

EMPLOYABILITY | 39. expand social capital and social networks | |

| 40. create new networks with peers and professionals | ||

| 41. increase the feeling of connection and belonging to a company/group | ||

| 42. create the opportunity to tap into the hidden job market. | ||

| 43. develop the ability to get industry insights and to accept the industry knowledge that people share with you. | ||

| 44. change behavior patterns and habits for better experiences, | ||

| 45. become flexible and adaptable to the new workplace culture. | ||

| 46. practice presentation skills | ||

| 47. improve personality | ||

| 48. learn a positive attitude to be more social. | ||

| 49. stand out and let people know about you | ||

| 50. make yourself more likable | ||

Table 3. University administrators’ perception of ECAs - questionnaire two

OBSTACLES FOR ECA EMPLOYMENT 1= Strongly disagree; 2= disagree; 3= neutral; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree |

1. Cost |

2. Time |

3. Management Capability |

4. Learning Program |

5. Students' Participation |

6. Former students |

7. University's Vision and Mission |

8. Employers/the Industries |

9. Local authorities |

POSSIBLE BENEFITS OF ECA EMPLOYMENT |

10. Increase attendance |

11. Promote the connectedness |

12. Increase cost |

13. Increase the admission rate |

14. Intervene the curriculum development |

15. Increase student commitment |

16. Promote a sense of discipline |

17. Lower the dropout rate |

18. Increase the graduates' employability rate |

19. Increase students' satisfaction towards the institution |

20. Upgrade the institution's credit rating |

Findings and discussions

Students' perceptions of ECAs

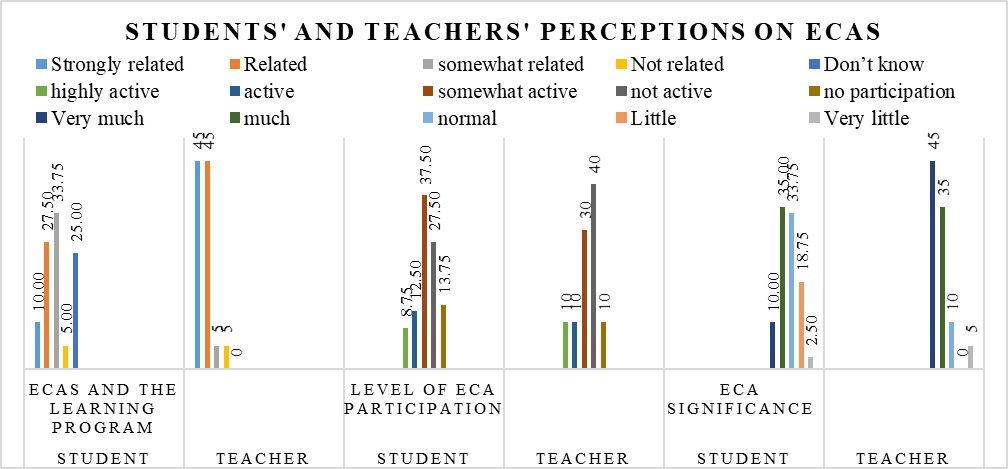

Statistical findings show that nearly three-quarters of the surveyed participants agreed that their ECAs were related to the learning program, but the level of relatedness was different. As much as 33.75% of the students said these two things were somewhat related, three times as much as the percentage that agreed on the close relation between them. It is noticeable that a quarter of them admitted they did not know if there was a link between the activities they got engaged in after school and what they formally learned in class. The findings about the participation level of ECAs were not quite rosy because active participants were outnumbered by inactive ones and those who did not participate. Figure 1 shows the students’ perception of ECA. Only 20% of the students considered themselves active partakers, while nearly 60% said they were not active. Those who had not yet got engaged occupied up to 13.75%. Students' belief about the importance of ECAs was also dissimilar to those who considered these activities important dominated. Only one-fifth of the total surveyed students did not find ECAs crucial in their life.

Figure 1. Students’ perception of ECAs in general

A closer look at the figures indicating how students thought of ECAs' influences on different aspects of their personal and academic development, we can realize that most of the students agreed that participation in ECAs allowed them to share their learning problems with peers and teachers and asked for their help (M=4.87; SD=0.37). These activities were also a source of inspiration for their learning (M=4.75; SD=0.58). However, the sampled students disagreed that they could focus on their learning after their involvement in ECAs (M=1.96; SD=0.33). Another thing is these students did not quite agree that the theoretical knowledge they were taught at university could be applied in reality through ECAs (M=2.95; SD=0.35).

Table 4. Students' perception of ECAs and student academic performance (N=80)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

SB1 | 2 | 4 | 2.95 | .352 | SB5 | 1 | 3 | 1.96 | .335 |

SB2 | 2 | 4 | 3.01 | .373 | SB6 | 3 | 5 | 4.75 | .585 |

SB3 | 3 | 5 | 4.06 | .368 | SB7 | 3 | 5 | 4.80 | .488 |

SB4 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .352 | SB8 | 3 | 5 | 4.87 | .369 |

As can be seen from the data provided in Table 4, the sampled students had the same viewpoint about skills development thanks to ECA participation. Although the mean scores attained were mostly the same, ranging from 3.99 to 4.13, the standard deviation figures significantly varied with a gap of 0.32. This statistical disparity indicated the disagreement among the surveyed students about the questions asked. Noticeably, the participants agreed that they could deal with uprising problems (SB9) and settle a conflict (SB12) easily, but they did not share this opinion among the participants (SD=0.1).

Table 5. Students’ perception of ECAs and skills development (N=80)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

SB9 | 3 | 4 | 3.99 | .112 | SB14 | 4 | 5 | 4.13 | .333 |

SB10 | 3 | 5 | 3.99 | .373 | SB15 | 3 | 5 | 4.04 | .434 |

SB11 | 3 | 5 | 4.06 | .368 | SB16 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .386 |

SB12 | 3 | 5 | 4.01 | .194 | SB17 | 3 | 5 | 4.07 | .414 |

SB13 | 3 | 5 | 4.10 | .377 | SB18 | 3 | 5 | 4.07 | .382 |

If there were striking similarities in the students' responses about the effects of ECAs on skills development, their thoughts of how these activities wielded influences on student engagement were of great difference. Most students conceded that engagement in ECAs promoted students' sense of discipline and self-regulation, leading to conformance to the university's regulations, norms, and expectations and improving the sense of belonging and connectedness to their institutions. Moreover, they believed that ECAs brought about chances for their interaction with peers and teachers. Through this, they could better their relationships and feel more engaged in their learning problem and where they were studying. Common beliefs and perceptions no longer existed when it comes to the questions of promoting students' persistence, efforts, and attention to learning (M=1.99; SD=0.34), the willingness and preference to master uphill tasks and challenges (M=2.99; SD=0.45). The information is provided in Table 6.

Table 6. Students’ perception of ECAs and student engagement (N=80)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

SB19 | 4 | 5 | 4.87 | .333 | SB24 | 4 | 5 | 4.89 | .318 |

SB20 | 3 | 5 | 4.00 | .421 | SB25 | 1 | 3 | 1.99 | .337 |

SB21 | 3 | 5 | 4.87 | .402 | SB26 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .386 |

SB22 | 3 | 5 | 4.90 | .341 | SB27 | 1 | 4 | 2.99 | .405 |

SB23 | 3 | 5 | 4.86 | .381 | SB28 | 2 | 4 | 3.10 | .377 |

Although the types and concepts of self-efficacy might have been understood differently by different students, almost all shared similar opinions about how ECAs could promote it. Table 7 shows that The participants in this survey reached a consensus on their ability to control behavior (self-regulatory efficacy) (M=4.06; SD=0.4), manage their learning activities (academic self-efficacy) (M=4.05; SD=0.39), do communal tasks (social self-efficacy) (M=4; SD=0.52), and engage in professional development (career self-efficacy) (M=4.81; SD=0.45) after they had taken part in various ECAs. Furthermore, they found themselves relaxing, more confident, and motivated in the pursuit of their academic goals.

Table 7. Students’ perception of ECAs and student self-efficacy

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

SB29 | 3 | 5 | 4.06 | .401 | SB34 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .314 |

SB30 | 2 | 5 | 3.95 | .525 | SB35 | 3 | 5 | 4.06 | .368 |

SB31 | 3 | 5 | 4.86 | .381 | SB36 | 3 | 5 | 4.80 | .488 |

SB32 | 3 | 5 | 4.81 | .453 | SB37 | 3 | 5 | 4.81 | .453 |

SB33 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .386 | SB38 | 3 | 5 | 3.94 | .401 |

Concerning the role of ECA participation in promoting employability for students, opinions diverged. Most of the students agreed that they could expand their social circles and create new networks with not only friends and teachers but also professionals and those who come from the industries. Partaking in ECAs provided them with the opportunities to get industry insights, put their future career into perspective, and tap into the hidden job market, thus improving their employability. Likewise, they were able to practice presentation skills, improve their personality, and become more adaptive to the future workplace culture. However, it is ludicrous to hear that the students did not agree that they could change their behavior patterns and habits for better experiences at the workplace (M=2.9; SD=0.42). In addition, they stated that getting involved in ECAs did not mean making themselves the center of attention, becoming a standout, letting people know about you, and making them like you. Table 8 shows the students perception of ECA and their impcats of employability.

Table 8. Students’ perception of ECAs’ impact on employability (N=80)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

SB39 | 3 | 5 | 4.77 | .527 | SB45 | 3 | 5 | 4.04 | .434 |

SB40 | 3 | 5 | 4.81 | .480 | SB46 | 3 | 5 | 4.00 | .390 |

SB41 | 3 | 5 | 4.80 | .513 | SB47 | 3 | 5 | 4.11 | .421 |

SB42 | 3 | 5 | 4.77 | .507 | SB48 | 3 | 5 | 3.95 | .501 |

SB43 | 4 | 5 | 4.88 | .333 | SB49 | 2 | 4 | 2.76 | .509 |

SB44 | 2 | 4 | 2.91 | .427 | SB50 | 2 | 4 | 3.04 | .462 |

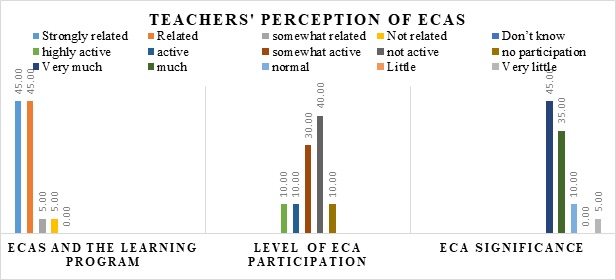

Teachers' perceptions of ECAs

As can be seen from Figure 2. teacher participants did not show the same results as the ones obtained from their students. The first disparity is that most of the teachers (90%) agreed upon the strong association between ECAs and the learning program, while their students did not. Another difference involved students' attitudes towards the significance of ECAs. While the student respondents felt hesitant to accept that ECAs were important for them, a large percentage of the surveyed teachers (80%) gave the thumbs up, perceiving ECAs as a pivotal component of students' learning program. A mere 5% rejected the necessity of ECAs at university. However, they reached a consensus on the level of ECA participation among students. A majority of the teachers (70%) and students (69%) disagree that their students were active ECA participants.

Figure 2. Teachers’ Perception of ECAs in general

Looking at Table 9, it is clear that opinions varied concerning the possibility that ECAs could better student academic performance, and there were also dissimilarities between teachers’ and students’ perception. The teacher respondents strongly agreed that their students had chances to discuss the learning problems they encountered in class (M=4.7; SD=0.47) with their friends and got academic support from peers, and this is the opinion shared by the student participants. What’s more, both teachers and students rejected students' ability to stay focused on learning thanks to the entry into ECAs

Table 9. Teachers’ perception of ECAs and student academic performance (N=20)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

TB1 | 2 | 4 | 3.65 | .587 | TB5 | 1 | 3 | 1.95 | .394 |

TB2 | 2 | 4 | 3.00 | .562 | TB6 | 2 | 5 | 3.95 | .510 |

TB3 | 2 | 4 | 2.85 | .489 | TB7 | 3 | 5 | 4.60 | .598 |

TB4 | 2 | 4 | 2.90 | .553 | TB8 | 4 | 5 | 4.70 | .470 |

The first difference was whether the science and theory could be learned through ECA participation. While most of the teachers believed in this achievement, their students were not quite sure about it. Another dissimilarity is the potential of their students to raise exam scores and GPA when taking part in ECAs. Students were quite sure of this; however, teachers' opinions were in between. Furthermore, teachers' perception of the impact of ECAs on students' skills development was not similar to their students'. While the teachers did not believe that their students could improve their communication and problem-solving skills via the ability to deal with uprising problems, settle a conflict, or gain a cutting edge in an argument, the students thought the opposite. Additionally, the teachers disapproved of their students’ ability to better time management skills and the research findings disclosed a disagreement among them (M=2.3; SD=0.74). On the contrary, the students stated that they could manage their time effectively, which got a consensus from the participants (M= 4.0; SD=0.43). Table 10 shows this perception.

Table 10. Teachers’ perception of ECAs and skills development (N=20)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

TB9 | 1 | 3 | 2.00 | .459 | TB14 | 3 | 5 | 4.20 | .523 |

TB10 | 2 | 5 | 3.95 | .686 | TB15 | 1 | 4 | 2.30 | .733 |

TB11 | 3 | 5 | 4.00 | .562 | TB16 | 2 | 5 | 3.25 | .639 |

TB12 | 2 | 4 | 3.00 | .459 | TB17 | 2 | 4 | 3.20 | .616 |

TB13 | 2 | 4 | 3.10 | .447 | TB18 | 3 | 5 | 4.10 | .447 |

Regarding student engagement, teacher participants' responses bear a striking resemblance to those collected from their students. They strongly agreed that student engagement could improve, and this was shown through the possibility of promoting students' sense of discipline, peer and teacher interaction, and a sense of belonging and relatedness. However, one difference that could be noticed is concerned with student self-regulation. Contrary to students' admission that they could monitor and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior to achieve their goals, both academic and non-academic ones, their teachers were not quite sure about this. Another dissimilar viewpoint is students' willingness to cope with difficulties or challenges. While the teachers turned down the possibility that their students could better this sort of skill, the students were not certain about it.

Table 11. Teachers’ perception of ECAs and student engagement (N=20)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

TB19 | 3 | 5 | 4.55 | .605 | TB24 | 3 | 5 | 4.20 | .616 |

TB20 | 3 | 5 | 3.40 | .598 | TB25 | 1 | 4 | 2.20 | .696 |

TB21 | 3 | 5 | 4.25 | .639 | TB26 | 3 | 5 | 3.90 | .553 |

TB22 | 4 | 5 | 4.65 | .489 | TB27 | 1 | 4 | 2.20 | .768 |

TB23 | 4 | 5 | 4.55 | .510 | TB28 | 2 | 4 | 2.25 | .550 |

The story was not much different regarding students' and teachers' perceptions of the improvement in student self-efficacy thanks to ECAs. Similarities could be observed in the findings about students' chances to improve mood, increase resilience, and better physical and mental health after taking part in ECAs, with mean scores of around four and SD being over 0.33. Opinions about the achievement of self-regulatory efficacy, career efficacy, and social efficacy were also the same when both of the participant groups had faith in this potential. However, differences could be detected in terms of academic efficacy. The students concurred with each other in managing their learning tasks even though they spent time doing ECAs; their teachers, however, dissented (M=2.25; SD=0.63) which are provided in Table 12.

Table 12. Teachers’ perception of ECAs and student self-efficacy (N=20)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

TB29 | 2 | 5 | 3.85 | .671 | TB34 | 2 | 5 | 3.15 | .587 |

TB30 | 2 | 5 | 3.85 | .671 | TB35 | 2 | 5 | 3.20 | .696 |

TB31 | 2 | 5 | 4.70 | .733 | TB36 | 3 | 5 | 4.05 | .394 |

TB32 | 3 | 5 | 4.70 | .571 | TB37 | 3 | 5 | 4.00 | .324 |

TB33 | 1 | 4 | 2.25 | .639 | TB38 | 3 | 5 | 4.60 | .598 |

Much was shared about the perception of two respondent groups regarding employability skills. Teachers and their students agreed that those who came in ECAs could reap the benefits from the expansion of their social circle, the new networks set with peers and professionals, the possibility to gain entry into the competitive labor market, the potential to get the industry insights and put their future career into perspective. They also shared the belief that the students who played an active part in ECAs did not aim to become standout and more likable. However, they did not agree with each other in the feedback they provided about the chances to practice presentation skills, improve personality, and change behavior patterns and habits. While the students confirmed the positive impacts the ECAs exerted on these aspects (M=4; SD=4), their teachers wavered in this opinion (M=2; SD=1.05). Table 13 shows the perception of ECAs and employability.

Table 13. Teachers’ perception of ECAs and employability (N=20)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

TB39 | 3 | 5 | 4.70 | .657 | TB45 | 1 | 5 | 2.50 | 1.051 |

TB40 | 3 | 5 | 4.75 | .550 | TB46 | 3 | 5 | 4.15 | .587 |

TB41 | 3 | 5 | 4.70 | .657 | TB47 | 2 | 5 | 3.00 | .649 |

TB42 | 3 | 5 | 4.70 | .657 | TB48 | 2 | 4 | 3.10 | .553 |

TB43 | 4 | 5 | 4.80 | .410 | TB49 | 2 | 4 | 2.80 | .523 |

TB44 | 1 | 4 | 2.35 | .875 | TB50 | 2 | 4 | 2.90 | .553 |

Administrators' perceptions of ECAs

To examine the perception of university administrators, 20 statements were provided, asking for two different aspects: the obstacles faced (C1-C9) and the benefits gained (C10-C20). The results are shown in Table 14 and Table 15, respectively.

Table 14. Administrators’ perception of the obstacles to employ ECAs (N=10)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

C1 | 4 | 5 | 4.70 | .483 | C6 | 1 | 5 | 3.30 | 1.252 |

C2 | 2 | 4 | 2.50 | .850 | C7 | 3 | 5 | 4.30 | .823 |

C3 | 1 | 4 | 2.30 | .949 | C8 | 3 | 5 | 4.30 | .823 |

C4 | 3 | 4 | 3.20 | .422 | C9 | 2 | 4 | 3.20 | .789 |

C5 | 4 | 5 | 4.80 | .422 |

|

|

|

|

|

To begin with the former, what stands out from the table was the spreading out of data, showing the disagreement among administrators coming from different universities. The largest standard deviation was 1.23, which was found in the response to the influences of former students on the employment of ECAs. The second is the figure about the hindrance resulted in by university management capability (C3). Feedback on the impact of time, employers, and local authorities was also different, with the standard deviation ranging from 0.83 to 0.85. While the administrators were not concerned about time and the university's mission and vision, they seriously considered the matter of cost and student participation. As shown in the Table 15.

Table 15. Administrators’ perception of the influences of ECAs on the institution (N=10)

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. |

C10 | 3 | 5 | 3.60 | .699 | C16 | 4 | 5 | 4.30 | .483 |

C11 | 4 | 5 | 4.40 | .516 | C17 | 2 | 5 | 4.00 | .816 |

C12 | 4 | 5 | 4.80 | .422 | C18 | 2 | 5 | 4.10 | .876 |

C13 | 2 | 4 | 3.60 | .699 | C19 | 4 | 5 | 4.50 | .527 |

C14 | 2 | 4 | 3.40 | .966 | C20 | 3 | 5 | 4.00 | .667 |

C15 | 3 | 4 | 3.20 | .422 |

|

|

|

|

|

The survey that examined university administrators' perception of the benefits of ECAs displayed similar statistical findings. Of 7 provided statements, 11 received agreement from the participants with mean scores of a bit over 4.0 and standard deviation ranging from 0.48 to 0.87. The most obvious benefit the universities might earn is the ability to increase a sense of relatedness and belonging and the possibility of increasing students' satisfaction rating towards their institutions. Other advantages could be to promote a sense of discipline, lower the dropout rate, increase graduates' employability, and upgrade the institutions' credit rating. In the long run, these positive outcomes would increase attendance rates and profits for the institutions. According to the survey participants, there were also downsides to implementing ECAs at university. They proposed that cost (C12) was bound to increase and curriculum development might be intervened (C14).

Discussion

The research findings showed significant differences in the perception of teachers and students of ECAs. This fact could be attributed to several factors; however, the main rationale behind this may be the roles they played at their institutions. Teachers were those who had to keep track of the implementation of ECAs and be responsible for its outcome, therefore, they might have been more positive about this part of the curriculum. In the meantime, students were those who participated in these activities and were directly or indirectly affected so that they might view them differently. The difference was noted via the big gap in the data collected regarding the connectedness between ECAs and the learning program. Another paradox is the contrast between the perceptions of both students and teachers of the importance of ECAs and the actual participation rate. This comparison is provided in the Figure 3. Only 20% of the students did not acknowledge the implementation of ECAs, and this rate was 10% of the teachers; however, the active participation rate viewed from both students' and teachers' perspectives was only 20%, half the inactive participation rate. Interviews conducted with the participation of eight students and four teachers randomly taken from four universities involved in the survey revealed that students often made excuses for their absence from ECAs, two primary reasons of which were their involvement in part-time jobs and home assignment overload.

Figure 3. Comparison of students’ and teachers’ perceptions on ECAs

Looking in detail, there were both similarities and discrepancies concerning the impacts of ECAs on student development. Though both teachers and students agreed on academic support of ECAs, they did not reach a consensus on the actual improvement of students' learning scores or GPAs. This went against the conclusions of Toyokawa and Toyokawa (2002), Wilson (2009), and Sullivan (2018) about the achievements their students made after their involvement in ECAs. The sources of ECAs’ contribution to students' academic success were not the same as some earlier studies concluded. The interviewed students replied that they could learn better because of the inspiration they got from ECAs, and the more they relaxed with these activities, the more they were encouraged to learn. Moreover, they admitted that the sense of belonging or connectedness (Cosden et al., 2004) helped them retain their school education. The bond they could develop with peers and teachers (Toomey & Russell, 2013) supported them to engage in learning. The knowledge they attained from their participation in ECAs was essential but not enough and even sometimes not quite relevant to their formal programs or tests. The desire to keep their public face drove them to make major strikes in learning.

In addition to the relationship between academic achievements and ECAs, skills enhancement is one of the top priorities in studies of the impacts of these activities in an educational setting. Findings showed a complete agreement among the sampled students of ECAs' good influence on the development of various skills. Their better problem-solving skills were evidenced by their ability to deal with difficulties, willingness to take over uphill tasks, or self-confidence in setting a conflict. What's more, their good teamwork and communication skills were shown via the rapport they could build up with stakeholders both inside and outside the university. Critical thinking and leadership skills, which were hard to achieve during their formal classes, could be nurtured by the involvement in ECAs. All of these strengthened the earlier findings about the positive effects of ECAs on skills development (Annu & Sunita, 2014; Buckley & Lee, 2021; Lyoba & Mwila, 2022). However, the teachers' failure to confirm is a matter of concern. Unless the teachers kept an eye on their students' participation in ECAs and observed their progress, it would be challenging for them to evaluate the improvements their students made. Another point worth mentioning is that the teachers did not believe in their students' potential to change for the better through off-campus activities.

In this study, the findings about student engagement were in line with those previously published (Astin, 1984; Fredricks et al., 2004). Both the teacher and student respondents shared their opinions about the good learning outcomes as well as the positive attitudes of students brought about by their participation in ECAs. This completely aligned with the proposals of Astin (1984) and Braxton et al. (2000). However, considering student self-efficacy, we can realize some mismatches between the findings of this study and those of previous publications. While Huang and Chang (2004), Stephens and Schaben (2002), Griffiths et al. (2021), Bekomson et al. (2020), and many other researchers confirmed the positive correlation between ECAs and student self-efficacy, the teachers of this survey not agree that students' engagement in ECAs could promote their efficacy, especially the academic type. Interviewing the teachers partly shed light on this matter. The interviewees said their students cannot have been able to spend a sufficient amount of time on learning as much of their time budget was used to fulfill the requirements of ECAs. From their observations, the more their students were engrossed in ECAs, the more chance their absenteeism was. They also missed home assignment deadlines, used ECAs as an excuse for their low academic scores, and came to class with tired faces. These answers appeared to go against Dinther et al. (2011), who believed that ECA participants stayed motivated in the pursuits of their academic goals and made learning progress.

Though largely similar, Opinions on the facilitation of students' employability through ECAs followed two streams. The ones that involved the possibility for students to set foot in the industries and the labor market were evident and analogous to earlier publications (Shaffer, 2019; Clark et al., 2015; Hui et al., 2021); however, the perceptions of students' ability to change and become more adaptable to the job market, to improve their personality, and to be more outstanding and likable were not supported by the previous studies (Greenbank, 2015; Keenan, 2010; Thompson et al., 2013).

The final point to mention in this paper is about university administrators' perceptions of ECAs. Although the research findings revealed significant variations in the responses collected, it is worthwhile to mention the consensus attained regarding the impacts of ECAs on the institution, with the merits outweighing the downsides. The belief that ECAs could reduce the dropout rate while raising the admission rate could change the existing culture of employing ECAs in universities in Vietnam. In addition to the mission of gaining excellence in intellectual and professional training, tertiary institutions in this country need to care about their prestige and budget, which are sure to be strongly affected by student admission and student retention. Another point is the increase in students' satisfaction and credit rating of an institution, both of which received strong approval from the participants. If these two aspects were not a concern of university administrators in the old days, they have become mandatory criteria for university accreditation in Vietnam.

Conclusion

Both teachers and students did not always reach an agreement about the way they perceived ECAs as a part of university curriculum development. This study further strengthens the belief that ECAs benefit students both academically and non-academically. Students can make full use of the time they spend working with others towards the fulfillment of an ECA because their academic performance stands a great chance to be improved, their self-confidence is destined to be boosted, and their skills, various as they are, are bound to be promoted, and their engagement in learning and their institutions are certain to increase. However, mismatches between teachers' and students' perceptions should be reconsidered. The teacher participants appeared to be alienated from the application of ECAs and were not certain about the outcomes it generated. Meanwhile, the student participants felt rosy about their engagement in these extra duties after school. While carrying out ECAs at university is not an uphill task, according to the university administrators, and the advantages this policy is expected to bring out are not negligible, the low participation rate of ECAs at the surveyed institutions remained a great concern.

References

Annu, S., & Sunita, M. (2014). Extracurricular activities and student's performance in secondary school. International Journal of Technical Research and Applications, 2(6), 8-11. www.ijtra.com

Asmal, K. (2000). Protocol for the organization, management, coordination, and monitoring of school music competitions and/or festivals for schools in South Africa. Government Notice No. 21697, 424(1079), 1-12.

Astin, A. (1984). Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518-529. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220017441

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman and Company

Bandura, A. (1989). Self-regulation of motivation and action through internal standards and goal systems. In L.A. Pervin (Ed.), Goal concepts in personality and social psychology, 19-38. Earlbaum. https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=147269

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 50, 248-287.

Bartkus, K. R., Nemelka, B., Nemelka, M., & Gardner, P. D. (2012). Clarifying the meaning of extracurricular activity: A literature review of definitions. American Journal of Business Education, 5(6), 693-704. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v5i6.7391

Bekomson, A. N., Amalu, M. Ngban, A., & Kinsley, A. B. (2020). Interest in Extra Curricular Activities and Self Efficacy of Senior Secondary School Students in Cross River State, Nigeria. International Education Studies, 13(8), 79-87. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v13n8p79

Borman, M., & Spring, H. (1995). Schools in central cities: Structure and Process. Longman.

Boyatzis, R. E. (2008). Competencies in the 21st century. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840730

Braxton, J. M., Milem, J. F., & Sullivan, A. S. (2000). The Influence of Active Learning on the College Student Departure Process: Towards a Revision of Tinto's Theory. Journal of Higher Education, 71, 569-590.

Bryson, M.J. (2004). What to do when stakeholders matter: A guide to stakeholder identification and analysis techniques. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228940014

Buckley, P., & Lee, P. (2021). The impact of extra-curricular activity on the student experience. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(1), 37-48. http://doi.org/10.1177/1469787418808988

Camp, W. (1990). Participation in student activities and achievement: A covariance structural analysis. Journal of Educational Research, 83, 272-278. https://www.academia.edu/37216152/

Chia, Y. M. (2005). Job offers of multi-national accounting firms: The effects of emotional intelligence, extracurricular activities, and academic performance. Accounting Education, 14(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/0693928042000229707

Cherry, K. (2023, Feb 27). Self Efficacy and Why Believing in Yourself Matters. verywellmind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-self-efficacy-2795954#:~:text=Self%2Defficacy%20is%20a%20person's,the%20pursuit%20of%20their%20goal.

Clark, G., Marsden, R., Whyatt, J. D., Thompson, L., & Walker, M. (2015). 'It's everything else you do …': Alumni views on extracurricular activities and employability. Active Learning in Higher Education, 16(2), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787415574050

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1985). Research methods in education (2nd Ed). Croom Helm, Ltd

Cosden, M., Morrison, G. M., Gutierrez, L., & Brown, M. (2004). The Effects of Homework Programs and After-School Activities on School Success. Theory Into Practice, 43(3), 220-226. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4303_8

Craft, S. W. (2012). The impact of extracurricular activities on student achievement at the high school level (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Southern Mississippi. https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1567&context=dissertations

Dinther, M. V., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. R. (2011). Factors affecting students' self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003.

Diniaty, A., & Kurniati, A. (2014). Students' Extracurricular Activities in Higher Education and Its Effect on Personal Development and Academic Achievement. Al-Ta'lim Journal, 20(3), 161-173. https://doi.org/10..15548/jt.v21i3.96

Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. National Center for Education Statistics.

Freeman, E.R. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman

Fredricks, A.J., Blumenfeld, C.P., & Paris, H.A. (2004). School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research. 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006a). Extracurricular Involvement and Adolescent Adjustment: Impact of Duration, Number of Activities, and Breadth of Participation. Applied Developmental Science, 10(3), 132-146. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads1003_3

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006b). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698-713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012- 1649.42.4.698

Fung, D., Lee, W., & Chow, C. (2007). A feasibility study on the personal development planning process embedded at the 'Special'ePortfolio for generic competencies development. European Institute for E-Learning (EIFEL), 332-340.

Greenbank, P. (2015). Still focusing on the 'essential 2:1': Exploring student attitudes to extra-curricular activities. Education + Training, 57(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2013-0087

Griffin, M. M., & Griffin, W. M. (1998). An Investigation of the Effects of Reciprocal Peer Tutoring on Achievement, Self-Efficacy, and Test Anxiety. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23(3), 298-31. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.0971

Griffiths, T. L., Dickinson, J., & Day, C. (2021). Exploring the relationship between extracurricular activities and student self-efficacy within a university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(9), 1294-1309, http://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1951687

Haste, H. (2001). Ambiguity, autonomy, and agency: Psychological challenges to new competence. In D. Rychen & L. Salganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies (pp. 93-120). Hogrefe & Huber

Huang, Y. R., & Chang, S. M. (2004). Academic and co-curricular involvement: Their relationship and the best combinations for students' growth. Journal of College Students' Development, 45(4), 391-406. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2004.0049

Hunt, D. H. (2005). The effects of extracurricular activities in the educational process: Influence on academic outcomes. Sociological Spectrum, 2, 417-445. https://doi.org/10.1080/027321790947171

Iddrisu, M. A., Senadjki, A., Ogbeibu, S., & Senadjki, M. (2023). Inclination of student participation in extra-curricular activities in Malaysian universities. SCHOLE: A Journal of Leisure Studies and Recreation Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/1937156X. 2023.2166437

Jane, D., Cariaga, N., & Molina, J. (2016). The Impact of Extra-Curricular Activities in the Personal Development of the Members of Performing Groups of Philippine Normal 101 University-North Luzon. International Journal of World Research, 1(25), 74-90. https://dokumen.tips/documents/the-impact-of-extra-curricular-activities-in-the-apjorcomijrpdownloads-student.html?page=6

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2012). New learning: Elements of a science of education. Cambridge University Press.

Kasunic, M. (2005). Designing an Effective Survey. Carnegie Mellon University

Keenan, L. (2010). The effect of extracurricular activities on career outcomes: Literature review. Student Psychology Journal, 1, 149-162. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/HE-EFFECT-OF-EXTRACURRICULAR-ACTIVITIES-ON-CAREER-%3A/3be7cdbe50a6dd0e3f19beefb2da4d27f7f91a16

Kuh, G. D. (2001). Assessing What Matters to Student Learning: Inside the National Survey of Student Engagement. Change, 33(3), 10-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091380109601795

Lam, Y. L. J., & Pang, S. K. N. (2003). The relative effects of environmental, internal and contextual factors on organizational learning: The case of Hong Kong schools under reforms. The Learning Organization, 10(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470310462094

Lamborn, S.D., Brown, B.B., Mounts, N.S., & Steinberg, L. (1992). Putting School in perspective: The influence of family, peers, extracurricular participation, and part-time work on academic engagement. In Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools (Chapter 6).

Lee, B., & Vondracek, W.F. (2014) Teenage goals and self-efficacy beliefs as precursors of adult career and family outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 85(2), 228-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.06.003

Leedy, P.D., & Ormrod, J.E. (2005) Practical Research: Planning and Design. Prentice Hall.

Leung, C., Raymond Ng, C., & Chan, P. (2011). Can Co-curricular Activities Enhance the Learning Effectiveness of Students?: An Application to the Sub-degree Students in Hong Kong. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 329-341.

Lyoba, M. A., & Mwila, M. P. (2022). Effectiveness of Extracurricular Activities on Students' Learning Processes in Public Secondary Schools in Sikonge District, Tanzania. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 28(2), 27-38. http://doi.org/10.9734/AJESS/2022/v28i230673

Mahoney, J. L., & Cairns, R. B. (1997). Do extracurricular activities protect against early school dropout? Developmental Psychology, 33, 241-253. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.241

Margolis, H., & McCabe, P. P. (2006). Improving Self-Efficacy and Motivation: What to Do, What to Say. Intervention in School and Clinic, 41, 218-227. https://doi.org/10.1177/10534512060410040401

McNeal, R. B. (1999). Participation in Extracurricular activities: Investigating school effects. Social Science Quarterly, 80(2), 291-309. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42863901

Mitchell, R., Agle, B., & Wood, D. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853-886. https://www.jstor.org/stable/259247

Munir, S., & Zaheer, M. (2021). The role of extra-curricular activities in increasing student engagement. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 16(3), 241-254. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-08-2021-0080

Nunan, D. (1991). Research Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge

Olibie, E. I., & Ifeoma, M. (2015). Curriculum Enrichment For 21st Century Skills: A Case for Arts Based Extra-Curricular Activities for Students. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 6(1), 4850-4856. http://www.recentscientific.com/current-issue

Pajares, F., & Urdan, T. (Eds.) (2006). Self-efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Information Age Publishing

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2006). How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research (Vol. 2). Journal of College Student Development, 47(5), 589-592. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0055

Piirto, J. (2011). Creativity for 21st century skills: How to embed creativity into the curriculum. Rotterdam, Sense Publishing.

Pike, G. R. (2006). The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of NSSE Scalet Scores. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 551-564.

Matkovic, P., Tumbas, P., Sakal, M., & Pavlićević, V. (2014). University stakeholders in the analysis phase of the curriculum development process model. 7th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI 2014) November 2014. Seville, Spain. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272294393

Shaffer, M. L. (2019). Impacting student motivation: Reasons for not eliminating extracurricular activities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 90(7), 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2019.1637308

Shulruf, B. (2010). Do extra-curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56(5-6), 591-612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9180-x

Snellman, K., Silva, J. M., & Putnam, R. D. (2015). Inequity outside the classroom: Growing class differences in participation in extra-curricular activities. Voices in Urban Education, 40, 7-14. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1056739

Stephens, L. J., & Schaben, L. A. (2002). The effect of interscholastic sports participation on academic achievement of middle-level school students. Nassp Bulletin, 86(630), 34-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263650208663005

Sullivan, P. (2018). Extra-curricular activities in English secondary schools: What are they? What do they offer participating students? How do they inform EP practice? Doctoral thesis (D. Ed. Psy), UCL (University College London). https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10053701/

Thompson, L. J., Clark, G., Walker, M., & Whyatt, D. (2013). It's just like an extra string to your bow: Exploring higher education students' perceptions and experiences of extracurricular activity and employability. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787413481129

Toomey, R. B., & Russell, S. T. (2013). An Initial Investigation of Sexual Minority Youth Involvement in School‐Based Extra-curricular Activities. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 304-318. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3811967/

Toyokawa, T., & Toyokawa, N. (2002). Extracurricular activities and adjustment of Asian international students: A study of Japanese students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26(4), 363-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00010-X

Umeh, Z., Bumpus, P. J., & Harris, L. A. (2020). The impact of suspension on participation in school-based extracurricular activities and out-of-school community service. Social Science Research, 85, 102-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102354

Vinas-Forcade, J., Mels, C., Valcke, M., & Derluyn, I. (2019). Beyond academics: Dropout prevention summer school programs in the transition to secondary education. International Journal of Educational Development, 70, 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102087

Wilson, N. (2009). Impact of extracurricular activities on students. https://www2.uwstout.edu/content/lib/thesis/2009/2009wilsonn.pdf

World Bank. (2019). Russian Federation: Doing Extra-Curricular Education: Blending traditional and digital activities for equitable learning. 1–7. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/341991561976813788/pdf/RussianFederation-Doing-Extra-Curricular-Education-Blending-Traditional-and-DigitalActivities-for-Equitable-Learning.pdf

Hui, Y. K., Kwok, F. F., & Shing, H. H. (2021). Employability: Smart learning in extracurricular activities for developing college graduates' competencies. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(2), 171-188. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6734

Yousry, N. (2022). Policy Evaluation of the role of Extracurricular activities on students' Character building and Academic Excellence: A Case Study of Cairo's Schools [Master's Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1974

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663-676. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163261

Download Count : 93

Visit Count : 562

Keywords

Extracurricular Activities; Perception; Stakeholders; Tertiary Level

How to cite this article:

Lien, T. T, N. (2024). Stakeholder Perception of Extracurricular Activities at the Tertiary Level in Vietnam. Studies in Educational Management, 15, 35-59. https://doi.org/10.32038/sem.2024.15.03

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interests

No, there are no conflicting interests.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/