Original Research

Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction among Female Nurses: The Moderating Role of Social Support in Ghana’s Health Sector

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

Work-Family Conflict (WFC) has become a pressing concern in health systems worldwide, particularly for nurses whose professional and domestic roles often overlap. In Ghana, where traditional gender roles assign caregiving responsibilities to women, female nurses face unique challenges balancing work and family life. This study investigates the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among female nurses, particularly the moderating role of social support from supervisors, co-workers, and family members. Guided by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, the study employs a quantitative, survey-based design involving 210 female nurses across three major hospitals in Ghana’s Western Region. Using validated instruments, data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics to test hypotheses regarding the associations among WFC, job satisfaction, and sources of social support. Results indicate that higher levels of work-family conflict significantly reduce job satisfaction, but social support moderates this relationship. Supervisor and co-worker support showed stronger buffering effects than family support, though all three forms of support contributed positively. The study underscores the need for organizational and policy interventions to enhance social support mechanisms and mitigate the negative effects of work-family conflict on nurses’ professional satisfaction. The findings contribute to the literature by situating the work-family interface within an African cultural and healthcare context and provide practical recommendations for policymakers, hospital administrators, and practitioners.

Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction among Female Nurses: The Moderating Role of Social Support in Ghana’s Health Sector

Fred Aboagye1, Emmanuel Erastus Yamoah2

1Local Government Service, Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana

2University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

Abstract:

Work-Family Conflict (WFC) has become a pressing concern in health systems worldwide, particularly for nurses whose professional and domestic roles often overlap. In Ghana, where traditional gender roles assign caregiving responsibilities to women, female nurses face unique challenges balancing work and family life. This study investigates the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among female nurses, particularly the moderating role of social support from supervisors, co-workers, and family members. Guided by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, the study employs a quantitative, survey-based design involving 210 female nurses across three major hospitals in Ghana’s Western Region. Using validated instruments, data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics to test hypotheses regarding the associations among WFC, job satisfaction, and sources of social support. Results indicate that higher levels of work-family conflict significantly reduce job satisfaction, but social support moderates this relationship. Supervisor and co-worker support showed stronger buffering effects than family support, though all three forms of support contributed positively. The study underscores the need for organizational and policy interventions to enhance social support mechanisms and mitigate the negative effects of work-family conflict on nurses’ professional satisfaction. The findings contribute to the literature by situating the work-family interface within an African cultural and healthcare context and provide practical recommendations for policymakers, hospital administrators, and practitioners.

Keywords: Work-Family Conflict, Job Satisfaction, Social Support, Female Nurses, Stress and Coping

Introduction

Balancing professional and family responsibilities has become an increasingly pressing challenge in today’s workforce. Across industries, employees struggle to manage the competing demands of career advancement, organizational expectations, and familial duties. Nowhere is this tension more evident than in the health sector, where employees, particularly nurses, are expected to work long, irregular hours in highly stressful environments while simultaneously fulfilling substantial family responsibilities (Fletcher et al., 2022).

Nurses represent the backbone of healthcare systems worldwide, providing direct patient care, emotional support, and clinical expertise that ensure effective treatment outcomes. Yet, these professional demands often conflict with personal obligations. This conflict is particularly acute for women, who constitute the majority of the global nursing workforce and are simultaneously expected to shoulder primary caregiving and household responsibilities (Akter et al., 2019). In Sub-Saharan Africa, and Ghana specifically, cultural norms reinforce this dual burden, as women are socially positioned as nurturers and caretakers, even when engaged in demanding full-time employment (Ametorwo & Ofori, 2014).

Within the Ghanaian context, the strain on female nurses is compounded by systemic challenges in the health sector, including inadequate staffing, resource constraints, and heavy patient loads. These institutional pressures increase working hours and intensify role conflict between work and family. Consequently, many female nurses find themselves navigating a persistent state of Work-Family Conflict (WFC), defined as a form of inter-role conflict where role pressures from work and family domains are mutually incompatible (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

The consequences of WFC are significant for both employees and organizations. At the individual level, research consistently demonstrates that WFC undermines job satisfaction, increases stress, and leads to burnout (Mauno & Ruokolainen, 2017; Otoo et al., 2023; Ozduran et al., 2025; Raffenaud et al., 2020). At the organizational level, dissatisfaction among nurses is strongly associated with reduced productivity, higher absenteeism, turnover intentions, and ultimately, compromised patient care outcomes (Lambert et al., 2020). In a healthcare system already strained by workforce shortages, the implications of job dissatisfaction among nurses are particularly severe. Although WFC research is important, studies in Ghana are limited. Previous research has looked at WFC among bankers (Ametorwo et al., 2021), hospitality workers (Gamor et al., 2018), and college tutors (Adibi, 2023), but there is little focus on healthcare professionals. This is a significant gap because nurses’ working conditions and societal expectations create unique and complex work-family conflict experiences. Filling this gap is especially important given the vital role nurses play in public health.

One factor that may buffer the negative effects of WFC on job satisfaction is social support. Social support refers to resources provided by supervisors, co-workers, and family members in the form of emotional encouragement, practical assistance, or flexible arrangements (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Studies suggest that social support reduces stress, enhances resilience, and improves job outcomes by helping employees manage competing demands (Barnett et al., 2019; Chan et al., 2016). However, findings have been inconsistent regarding the relative importance of supervisor, co-worker, and family support across different cultural and organizational contexts (Dodanwala & Shrestha, 2021; Goswami & Sarkar, 2022).

Against this backdrop, the present study investigates the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among female nurses in selected hospitals in Ghana’s Western Region. Specifically, the study explores whether social support moderates this relationship, with a focus on support from supervisors, co-workers, and family members.

Justification of the Study

This study is justified on several grounds. First, it contributes to the theoretical understanding of the work-family interface by applying the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) to the Ghanaian healthcare context. Viewing work-family conflict as a stressor and social support as a coping resource offers insight into how cultural and organizational factors shape nurses’ experiences.

Second, the study addresses a clear empirical gap. Although work-family conflict and job satisfaction have been widely explored in Western and Asian settings, limited research has examined these relationships in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among nurses. By focusing on Ghana, the study highlights how gender norms and resource-constrained health systems influence work-family dynamics.

Third, the study has practical relevance. Nurses’ job satisfaction affects patient outcomes, staff retention, and healthcare quality. Understanding how work-family conflict operates and identifying effective support mechanisms can guide hospital administrators and policymakers in designing interventions such as flexible scheduling, mentoring programs, and family-friendly workplace policies.

Finally, the study offers social value by drawing attention to the daily realities of Ghanaian women balancing demanding professional and domestic roles. Addressing the pressures they face is essential for promoting gender equity, nurse well-being, and sustainable healthcare delivery.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to explore how work-family conflict affects the job satisfaction of female nurses in selected hospitals in Ghana’s Western Region and to examine the extent to which social support from supervisors, co-workers, and family members shapes this relationship. In doing so, the study aims to provide a clearer understanding of how work and family pressures interact with supportive resources within the healthcare environment.

Objectives of the Study

The study seeks to examine the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among female nurses, while also exploring how different forms of social support shape this relationship. Specifically, it investigates whether supervisor support moderates the effect of work-family conflict on job satisfaction, considers the extent to which co-worker support influences this association, and evaluates whether family support serves as an additional moderating factor. Together, these objectives provide a comprehensive basis for understanding how work-family dynamics and available support systems affect the job satisfaction of female nurses in Ghana’s healthcare sector.

Literature Review

Concept of Work-Family Conflict

Work-family conflict is defined as a form of inter-role conflict where role pressures from work and family are mutually incompatible (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Şahin & Yozgat, 2024). It manifests in three forms: time-based conflict, strain-based conflict, and behavior-based conflict. Time-based conflict arises when time devoted to one role reduces availability for the other (Otoo et al., 2023). Strain-based conflict occurs when stress from one role hinders effective performance in another. Behavior-based conflict emerges when behavioral expectations in one role are incompatible with those in the other (French et al., 2018).

Nurses often encounter all three forms of conflict due to long shifts, emotional exhaustion, and the expectation to provide continuous care both at home and work. Studies show that persistent work-family conflict leads to stress, burnout, and decreased job satisfaction (AlAzzam et al., 2017; Anafarta, 2010).

Concept of Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is conceptualized as an employee’s positive emotional state resulting from appraisal of job experiences (Havens et al., 2018). It encompasses cognitive (evaluative) and affective (emotional) components (Soomro et al., 2018). For nurses, job satisfaction is influenced by intrinsic factors (e.g., recognition, autonomy, purpose) and extrinsic factors (e.g., pay, work conditions, social relations). High job satisfaction is linked to lower turnover, higher commitment, improved patient outcomes, and greater well-being (Lambert et al., 2020).

Concept of Social Support

Social support refers to resources provided by others through emotional, informational, or instrumental means (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Sharma & Yadav, 2021). Supervisor support includes empathy, flexibility, and facilitating work-life policies (French et al., 2018). Co-worker support entails sharing tasks, offering advice, and emotional encouragement (Leschyshyn & Minnotte, 2014). Family support provides emotional care and instrumental help outside work (Rathi & Barath, 2013).

Social support functions as a stress buffer, reducing the negative consequences of WFC on psychological outcomes, including job satisfaction (Barnett et al., 2019; Chan et al., 2016). However, studies show mixed results, with some sources of support (e.g., supervisors) more impactful than others (Goswami & Sarkar, 2022).

Theoretical Review: Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, developed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), is a widely applied framework for understanding how individuals perceive and respond to stressors. The model emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the individual and the environment, proposing that stress arises not solely from external pressures but from the individual’s appraisal of the situation and the perceived adequacy of coping resources. Within this framework, coping is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.

This theory has particular relevance to studies of work-family conflict, where employees are required to navigate the competing demands of work and family domains. In the case of nurses, the professional environment imposes time-based, strain-based, and behavior-based demands, while the family domain carries expectations of caregiving, nurturance, and domestic responsibilities. The mismatch between these two domains often results in conflict, which, according to the transactional model, is experienced as a stressor.

A central aspect of the model is the primary appraisal, where individuals evaluate whether a situation poses a threat, challenge, or is benign. For female nurses in Ghana, the simultaneous demands of patient care and family obligations are often appraised as threats to personal well-being and professional performance. The secondary appraisal involves assessing available resources to manage the stressor. Here, social support, whether from supervisors, co-workers, or family members, serves as a critical coping resource.

The model also highlights that stress outcomes, such as job dissatisfaction or burnout, are not inevitable; they depend on coping strategies and available resources. For instance, a nurse who receives flexible scheduling from a supervisor, emotional reassurance from family, and practical assistance from co-workers may perceive her situation as more manageable than one who lacks such support. Thus, the transactional model not only frames work-family conflict as a stressor but also situates social support as a moderating mechanism that mitigates its negative impact on job satisfaction.

This theoretical lens is particularly appropriate for the Ghanaian context, where cultural expectations intensify the role conflict experienced by women. By integrating stress appraisal and coping resources, the model provides a robust basis for examining how female nurses adapt to competing demands and why social support is pivotal in this adaptation process.

Empirical Review

Research on work-family conflict and job satisfaction has proliferated globally, though findings remain contextually varied. In developed countries, several large-scale studies confirm the negative association between WFC and job satisfaction. For example, Grandey et al. (2005) conducted a longitudinal study of dual-earner couples. They found that work interference with family predicted lower job satisfaction, while family interference with work was less significant. Similarly, Anafarta (2010), using data from Turkish health professionals, reported a low but significant negative correlation between WFC and job satisfaction. Labrague (2024) found that work-family conflict mediates the relationship between toxic leadership and job satisfaction among emergency nurses in the Philippines. AlAzzam et al. (2017) demonstrated that Jordanian nurses experiencing high WFC reported lower satisfaction, but this effect was buffered by supervisory support. Mauno and Ruokolainen (2017), in a study of Finnish professionals, also found that a lack of workplace support exacerbated the negative effects of WFC on satisfaction. Interestingly, Molina (2021) argued that in certain contexts, WFC does not significantly affect job satisfaction, highlighting the role of mediating variables such as job autonomy and cultural values.

African scholarship, though limited, has also shed light on these dynamics. Ametorwo and Ofori (2014) highlighted the persistent challenge of work-family balance among Ghanaian women entrepreneurs and employees, stressing that traditional gender norms exacerbate role conflict. Gamor et al. (2018) found that Ghanaian working parents reported high WFC, with significant implications for job satisfaction and well-being. However, very few studies have specifically targeted healthcare workers, despite evidence suggesting that nurses face unique pressures due to round-the-clock work schedules, emotional labor, and limited institutional resources (Asiedu et al., 2018).

Social support consistently emerges as a significant buffer. Chan et al. (2016) found that support from supervisors and family mediated the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction among Chinese workers. Barnett et al. (2019) similarly reported that workplace social support reduced psychological distress and enhanced satisfaction. However, the relative strength of different support sources varies. Goswami and Sarkar (2022) found that supervisor and co-worker support had stronger effects on job satisfaction than family support. Conversely, Dodanwala and Shrestha (2021) highlighted the importance of family support in reducing WFC among Nepalese workers.

These mixed results suggest that while the general relationship between WFC and job satisfaction is well established, the role of social support is context-dependent. Given the unique socio-cultural setting of Ghana, where women carry disproportionate domestic responsibilities, the moderating role of family, supervisor, and co-worker support warrants detailed exploration. This study therefore contributes to filling this empirical gap by situating the WFC - job satisfaction - social support nexus within the Ghanaian nursing profession.

Method

Research Paradigm and Approach

This study was grounded in the positivist research paradigm, which assumes that social phenomena can be objectively observed, measured, and analyzed to uncover patterns and causal relationships (Marsonet, 2019). Guided by this paradigm, the study adopted a quantitative research approach aimed at testing hypotheses derived from established theories on work-family conflict, job satisfaction, and social support. The use of quantitative methods allowed for objective measurement of variables, statistical examination of relationships, and generalization of findings across the population of female nurses (Saunders et al., 2009).

Research Design

A cross-sectional survey design was employed to collect standardized data from a large sample at a single point in time. This design was appropriate for identifying the associations among work-family conflict, job satisfaction, and social support, and for testing the hypothesized moderating effects within the nursing profession in Ghana. Surveys are widely recognized for their efficiency in capturing respondents’ perceptions and attitudes systematically (Check & Schutt, 2011).

Population and Sampling

The study population consisted of 460 female nurses employed in three major hospitals in Ghana’s Western Region, selected to represent diverse healthcare settings in the region. The Krejcie and Morgan (1970) formula was used to determine a representative sample size of 210 nurses, which provided sufficient statistical power for the intended analyses. A stratified random sampling technique was applied to ensure proportional representation across hospitals and departments (e.g., maternity, pediatric, emergency, and general wards). Within each stratum, respondents were randomly selected to minimize bias and enhance generalizability.

Conceptual and Operational Definition of Variables

Work-Family Conflict (WFC) conceptually refers to a form of inter-role conflict in which the demands of work and family roles are mutually incompatible, making participation in one role more difficult due to involvement in the other (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Operationally, WFC was measured using a 7-item scale adapted from Carlson et al. (2000). Respondents rated their agreement with statements such as “My work keeps me from my family activities more than I would like” on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for this construct was .94, indicating excellent reliability.

Job Satisfaction conceptually describes the extent to which employees feel content, fulfilled, and motivated by their work (Locke et al., 1976). Operationally, job satisfaction was assessed using 7 items adapted from Brayfield and Rothe (1951). Sample items included “I feel fairly satisfied with my present job.” Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was .75, confirming acceptable internal consistency.

Social Support was defined as the emotional, instrumental, or informational assistance individuals receive from others, which helps them manage stress and balance work-family demands (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Operationally, social support was measured using 12 items adapted from Caplan (1975), which covered three dimensions: supervisor support, coworker support, and family support. Sample items included “My supervisor is willing to listen to my personal problems,” “My co-workers help me when my workload is high,” and “My family members are understanding when I have to work late.” Items were rated on the same five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The composite Cronbach’s alpha for social support was .82, indicating good reliability.

Validity and Reliability

Content validity was ensured through expert review by two organizational behavior scholars and two hospital administrators, who confirmed that all items appropriately reflected the constructs under study. A pilot test involving 12 nurses was conducted to assess clarity and reliability, resulting in minor refinements to the wording. The Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of .70 (Cohen et al., 2017), confirming strong internal consistency.

Data Collection Procedure

Formal authorization was obtained from hospital management before data collection. The researchers met with nurse managers to explain the study’s objectives and obtain informed consent from participants. Questionnaires were distributed both in printed and digital form to accommodate varying schedules. Of the 234 questionnaires administered, 210 were validly completed, representing a response rate of 89.7%. Departmental coordinators assisted in managing the distribution process to reduce disruptions in patient care.

Data Analysis

The data collected were coded and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequencies) were used to summarize demographic data and construct distributions. Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess bivariate relationships among the key variables. To test the study hypotheses, hierarchical moderated regression analysis was employed following the procedures of Baron and Kenny (1986) and Hayes (2018) to examine whether supervisor, co-worker, and family support moderated the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction. Interaction terms (WFC × Support) were created after mean-centering the independent and moderator variables to minimize multicollinearity. Statistical significance was determined at p < .05.

Ethical Considerations

The study complied with the research and ethical guidelines of the University of Education, Winneba. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Confidentiality was assured through anonymized data handling, and findings were reported in aggregate form. Hospital authorities endorsed the study, and ethical protocols aligned with established guidelines for organizational and behavioral research (Van Wijk & Harrison, 2013).

Results

This section presents the study's findings in line with the stated objectives. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction and to test the moderating role of supervisor, co-worker, and family support.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Out of the 234 questionnaires distributed, 210 valid responses were retrieved, yielding a high response rate of 89.7%. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of respondents.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 210)

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency |

|

|

Age |

20–29 years |

58 |

|

|

30–39 years |

87 |

||

|

40–49 years |

48 |

||

|

50 years and above |

17 |

||

|

Marital Status |

Single |

62 |

|

|

Married |

126 |

||

|

Divorced/Separated |

14 |

||

|

Widowed |

8 |

||

|

Education |

Diploma |

91 |

|

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

103 |

||

|

Postgraduate |

16 |

||

|

Children |

No child |

41 |

|

|

1–2 children |

95 |

||

|

3–4 children |

60 |

||

|

5 or more children |

14 |

The majority of respondents were in their 30s (41.4%), married (60%), and had at least one child (80.5%). Nearly half of the respondents (49%) held a bachelor’s degree. These characteristics suggest a population balancing active professional and family responsibilities.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

Descriptive statistics were computed for all constructs, including means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha). Table 2 presents the results.

Descriptive statistics and reliability of study variables

|

Variable |

Items |

M |

SD |

Cronbach’s α |

|

Work-Family Conflict (WFC) |

7 |

3.72 |

.84 |

.94 |

|

Job Satisfaction (JS) |

7 |

3.21 |

.78 |

.75 |

|

Supervisor Support (SS) |

4 |

3.65 |

.91 |

.81 |

|

Co-worker Support (CWS) |

4 |

3.49 |

.86 |

.80 |

|

Family Support (FS) |

4 |

3.27 |

.89 |

.79 |

The mean score for WFC (M = 3.72, SD = .84) indicates that respondents experienced above-average levels of work-family conflict. Job satisfaction, however, was moderate (M = 3.21, SD = .78). Supervisor support (M = 3.65) was rated higher than co-worker (M = 3.49) and family support (M = 3.27), suggesting greater reliance on organizational than familial sources of support. All reliability coefficients exceeded the recommended threshold of .70, confirming internal consistency.

Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine relationships among variables. Results are presented in Table 3.

Correlation matrix of study variables (N = 210)

|

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. Work-Family Conflict |

1 |

||||

|

2. Job Satisfaction |

–.45** |

1 |

|||

|

3. Supervisor Support |

–.29** |

.39** |

1 |

||

|

4. Co-worker Support |

–.25** |

.33** |

.42** |

1 |

|

|

5. Family Support |

–.21* |

.28* |

.31** |

.29** |

1 |

*p < .05, **p < .01

The analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between WFC and job satisfaction (r = –.45, p < .01). Supervisor, co-worker, and family support all correlated positively with job satisfaction, with supervisor support showing the strongest association (r = .39, p < .01).

Before conducting the regression analysis, the necessary statistical assumptions were examined and found to be satisfactory. The distribution of residuals was approximately normal, with no significant deviation from normality. The relationship between the variables was linear, and the residual plots indicated constant variance, confirming homoscedasticity. The Durbin–Watson statistic (1.91) fell within the acceptable range, showing that the residuals were independent. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below 2.5, and the tolerance values were above .40, suggesting no multicollinearity among the predictors. Overall, the diagnostic checks indicated that all assumptions for multiple regression analysis were adequately met.

Regression Analysis

Direct Effect of WFC on Job Satisfaction

As presented in Table 4, a simple regression analysis showed that WFC significantly predicted job satisfaction (β = -.37, t = –7.25, p < .001), confirming Hypothesis 1 that higher WFC reduces job satisfaction. The model explained 21% of the variance in job satisfaction.

Regression of WFC on job satisfaction

|

Predictor |

β |

t |

p |

R² |

F |

|

Work-Family Conflict |

-0.37 |

-7.25 |

0.000 |

0.21 |

52.56** |

**p < .01

Moderating Role of Social Support

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the moderation effects of supervisor, co-worker, and family support. Interaction terms were computed (WFC × Support) and entered into the final models. Results are presented in Table 5.

Moderating effects of social support on the WFC–job satisfaction relationship

|

Predictor |

β |

t |

p |

R² |

ΔR² |

F |

|

Model 1: Supervisor Support |

||||||

|

WFC |

–.31 |

–6.12 |

.000 |

|||

|

Supervisor Support |

.27 |

5.41 |

.000 |

.32 |

.11 |

48.13** |

|

WFC × Supervisor Support |

.24 |

3.85 |

.001 |

|||

|

Model 2: Co-worker Support |

||||||

|

WFC |

–.28 |

–5.47 |

.000 |

|||

|

Co-worker Support |

.21 |

4.16 |

.000 |

.27 |

.06 |

36.45** |

|

WFC × Co-worker Support |

.18 |

2.67 |

.008 |

|||

|

Model 3: Family Support |

||||||

|

WFC |

–.25 |

–4.89 |

.000 |

|||

|

Family Support |

.19 |

3.72 |

.000 |

.23 |

.04 |

29.36** |

|

WFC × Family Support |

.14 |

2.13 |

.034 |

**p < .01

The results show that supervisor support significantly moderated the WFC–job satisfaction relationship (β = .24, p = .001), with the largest ΔR² = .11. Co-worker support also moderated the relationship (β = .18, p = .008), though with a smaller effect (ΔR² = .06). Family support showed the weakest moderating effect (β = .14, p = .034), with ΔR² = .04.

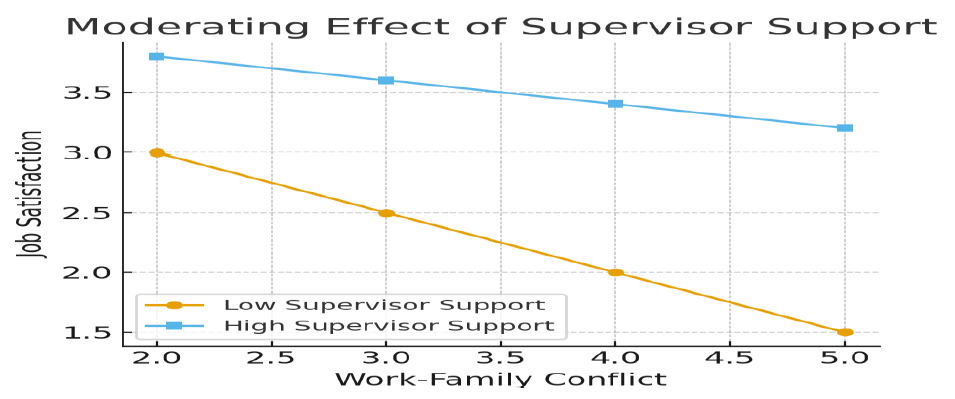

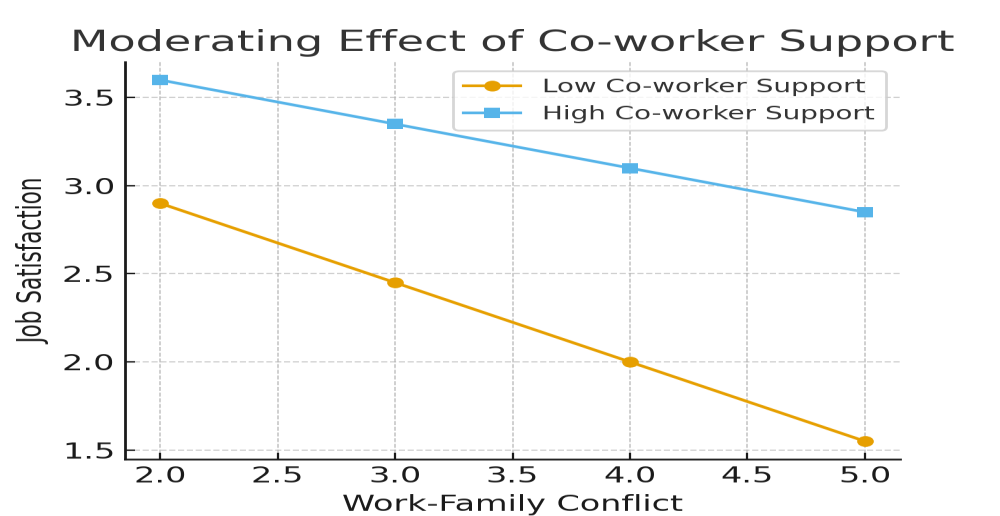

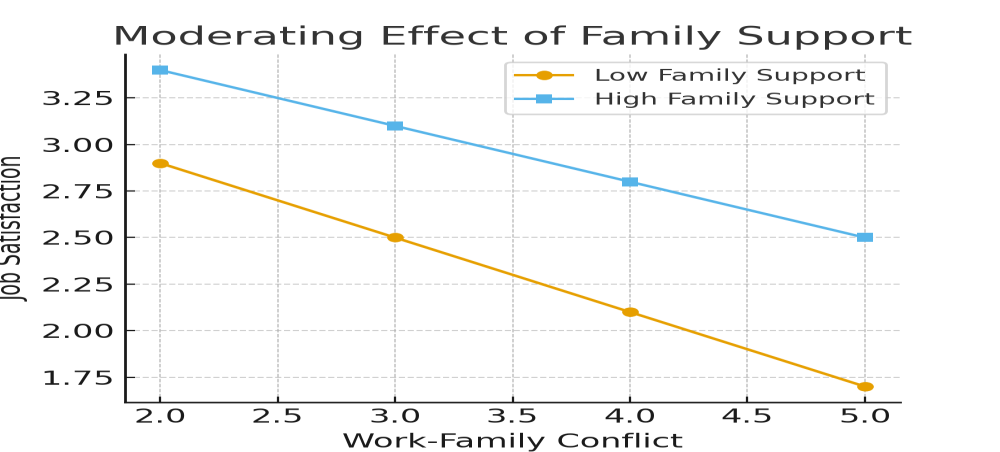

Figures 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the interaction effects of supervisor, co-worker, and family support on the relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction. The plots show that job satisfaction decreases as work-family conflict increases; however, this decline is considerably less steep when supervisor support is high, demonstrating a strong buffering effect. Co-worker support also mitigates the negative impact of work-family conflict on job satisfaction, though to a lesser extent than supervisor support. Family support shows a comparatively weaker moderating influence, as job satisfaction continues to decline noticeably with increasing work-family conflict, even when family support is high.

Moderating effect of supervisor support

Figure 2

Moderating effect of co-worker support

Figure 3

Moderating effect of family support

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between work-family conflict (WFC) and job satisfaction among female nurses in Ghana, focusing on the moderating effects of supervisor, co-worker, and family support. The results confirmed that WFC significantly reduces job satisfaction, and that different forms of social support help buffer this negative effect to varying degrees. These findings are consistent with the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which posits that stress arises when external demands exceed available coping resources. For female nurses, the combined pressures of demanding work schedules, staff shortages, and traditional caregiving roles amplify stress and diminish satisfaction with their jobs. The results demonstrated a strong negative relationship between WFC and job satisfaction, consistent with prior studies (Allen et al., 2000; Labrague, 2024; Mauno & Ruokolainen, 2017; Otoo et al., 2023), showing that competing role expectations undermine employees’ well-being. Within the Ghanaian context, nurses face high workloads, emotional strain, and cultural expectations that women must prioritize family care, creating constant tension between professional and personal responsibilities. These conditions make it difficult to achieve balance, resulting in diminished job satisfaction and potential burnout.

Social support emerged as a significant moderating factor in the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction. Consistent with the stress-buffering hypothesis (Cohen & Wills, 1985), higher levels of support mitigated the negative effects of WFC. Among the three forms of support examined, supervisor support exerted the strongest buffering influence. Supportive supervisors help reduce perceived conflict through flexible scheduling, equitable workload distribution, and emotional reassurance. This finding aligns with studies by Chan et al. (2016) and Goswami and Sarkar (2022), who emphasized that supportive leadership can counteract the strain caused by conflicting work and family demands. In Ghana’s health sector, where formal institutional supports are limited, supervisors serve as vital intermediaries who can enhance employees’ coping capacity.

Co-worker support also moderated the WFC-job satisfaction relationship, though less strongly than supervisor support. Given that nursing is highly collaborative, colleagues who share tasks and provide emotional encouragement help alleviate stress and improve morale. However, because co-workers have limited authority to alter schedules or workloads, their influence is primarily emotional and social rather than structural.

Family support showed the weakest moderating effect, suggesting that while families provide comfort and understanding, their support may not fully offset the pressures of demanding healthcare work. This contrasts with findings from South Asian contexts (e.g., Dodanwala & Shrestha, 2021), where family networks often play a larger buffering role. In Ghana, entrenched gender norms may constrain the extent of family assistance available to working women, as domestic expectations persist regardless of professional demands.

Theoretically, the study extends the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping into a Sub-Saharan African healthcare setting, demonstrating that work-family conflict functions as a significant stressor that undermines job satisfaction, and that organizational support is a critical coping resource. It also reveals cultural differences in the relative effectiveness of support types, highlighting that supervisor support is more influential than family support in contexts where institutional and cultural structures shape coping behaviors.

Practically, these findings suggest that healthcare institutions in Ghana should strengthen organizational-level mechanisms to manage work-family conflict. Training supervisors to adopt supportive leadership practices, promoting teamwork among nurses, and instituting family-friendly policies such as flexible scheduling, childcare support, and family leave can help mitigate the negative effects of WFC. Such initiatives would enhance nurses’ well-being, reduce turnover intentions, and improve healthcare service delivery.

Although this study provides valuable insights, it has certain limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts causal interpretation, and the reliance on self-reported data may introduce common method bias despite anonymity assurances. The study also focused on nurses in three hospitals within one region, limiting generalizability. Future research should consider longitudinal or mixed-methods approaches, broader samples across regions, and examination of other forms of support, such as organizational or community-based assistance.

This study affirms that work-family conflict significantly undermines job satisfaction among female nurses in Ghana, but supportive workplace relationships, especially with supervisors, play a vital role in mitigating these effects. The findings offer theoretical, practical, and policy insights that can guide healthcare administrators and policymakers in creating supportive work environments that foster both employee well-being and organizational effectiveness.

References

Adibi, M. G. D. (2023). Work-family conflict and its relationship with job satisfaction, family satisfaction, and social support among tutors in colleges of education, Ghana. African Journal for the Psychological Studies of Social Issues, 26(2).

Akter, A., Hossen, M. A., & Islam, M. N. (2019). Impact of work-life balance on organizational commitment of university teachers: Evidence from Jashore University of Science and Technology. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 7(04), 1073–1079. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v7i4.em01

AlAzzam, M., AbuAlRub, R. F., & Nazzal, A. H. (2017, October). The relationship between work–family conflict and job satisfaction among hospital nurses. Nursing forum, 52(4), 278–288).

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

Ametorwo, A. M. & Ofori, D. (2014). Work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict in a developing country. Developing Country Studies, 4(19), 133–139.

Ametorwo, A. M., Ofori, D., Annor, F., & Dartey-Baah, K. (2021). Work-family conflict as antecedent to workplace deviance: a study among bankers. African Journal of Management Research, 28(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajmr.v28i1.7

Anafarta, N. (2010). The relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(4), 168–177.

Asiedu, E. E. A., Annor, F., Amponsah‐Tawiah, K., & Dartey‐Baah, K. (2018). Juggling family and professional caring: Role demands, work–family conflict and burnout among registered nurses in Ghana. Nursing Open, 5(4), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.178

Barnett, R. C., Brennan, R. T., & Gareis, K. C. (2019). Social support, multiple roles, and women’s well-being: Evidence from a national sample. Women’s Health Issues, 29(1), 65–72.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-13085-001

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), 307–311.

Caplan, R. D. (1975). Job demands and worker health: Main effects and occupational differences. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

Chan, X. W., Kalliath, T., Brough, P., Siu, O. L., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Timms, C. (2016). Work-family enrichment and satisfaction: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work-life balance. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(15), 1751–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1075574

Check, J., & Schutt, R. K. (2011). Research methods in education. Sage Publications.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Validity and reliability. In Research methods in education (pp. 245-284). Routledge.

Dodanwala, T. C., & Shrestha, P. (2021). Work–family conflict and job satisfaction among construction professionals: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures, 29(2), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-11-2020-0042

Fletcher, K. A., Reddin, K., & Tait, D. (2022). The history of disaster nursing: from Nightingale to nursing in the 21st century. Journal of research in nursing, 27(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/17449871211058854

French, K. A., Dumani, S., Allen, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and social support. Psychological Bulletin, 144(3), 284.

Gamor, E., Amissah, E. F., Amissah, A., & Nartey, E. (2018). Factors of work-family conflict in the hospitality industry in Ghana. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(4), 482–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2017.1328263

Grandey, A., L Cordeiro, B., & C Crouter, A. (2005). A longitudinal and multi‐source test of the work–family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26769

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Goswami, M., & Sarkar, A. (2022). Work-family enrichment: Literature review. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 57(4).

Havens, D. S., Gittell, J. H., & Vasey, J. (2018). Impact of relational coordination on nurse job satisfaction, work engagement and burnout: Achieving the quadruple aim. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000587

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 607–610.

Labrague, L. J. (2024). Linking toxic leadership with work satisfaction and psychological distress in emergency nurses: the mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 50(5), 670–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2023.11.008

Lambert, E. G., Morrow, W., Hogan, N. L., & Vickovic, S. G. (2020). Exploring the association between work-family conflict and job involvement among private correctional staff. Journal of Applied Security Research, 15(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2019.1636591

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Leschyshyn, A., & Minnotte, K. L. (2014). Professional parents’ loyalty to employer: The role of workplace social support. The Social Science Journal, 51(3), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2014.04.003

Locke, E. A., Sirota, D., & Wolfson, A. D. (1976). An experimental case study of the successes and failures of job enrichment in a government agency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(6), 701.

Marsonet, M. (2019). Philosophy and logical positivism. Academicus International Scientific Journal, 10(19), 32–36.

Mauno, S., & Ruokolainen, M. (2017). Does organizational work-family support benefit temporary and permanent employees equally in a work-family conflict situation in relation to job satisfaction and emotional energy at work and family? Journal of Family Issues, 38(1), 124–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15600729

Molina, J. A. (2021). The work–family conflict: Evidence from the recent decade and lines of future research. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09700-0

Otoo, S., Dankwa, S., Annan-Nunoo, S., & Gyasi, K. (2023). An assessment of coping strategies on work-family conflict and job performance in Ghana. Universal Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.31586/ujssh.2023.734

Ozduran, A., Saydam, M. B., Eluwole, K. K., & Mertens, E. U. (2025). Work-family conflict, subjective well-being, burnout, and their effects on presenteeism. The Service Industries Journal, 45(3-4), 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2023.2209507

Raffenaud, A., Unruh, L., Fottler, M., Liu, A. X., & Andrews, D. (2020). A comparative analysis of work–family conflict among staff, managerial, and executive nurses. Nursing outlook, 68(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2019.08.003

Rathi, N., & Barath, M. (2013). Work‐family conflict and job and family satisfaction: Moderating effect of social support among police personnel. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(4), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-10-2012-0092

Şahin, S., & Yozgat, U. (2024). Work–family conflict and job performance: Mediating role of work engagement in healthcare employees. Journal of Management & Organization, 30(4), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.13

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson education.

Sharma, H., & Yadav, V. (2021). Linking supervisor and co-workers support to organizational commitment: Mediating effect of work-family conflict. Ramanujan International Journal of Business and Research, 6, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.51245/rijbr.v6i1.2021.277

Soomro, A. A., Breitenecker, R. J., & Shah, S. A. M. (2018). Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict, and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 7(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-02-2017-0018

Van Wijk, E., & Harrison, T. (2013). Managing ethical problems in qualitative research involving vulnerable populations, using a pilot study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 570–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200130

Download Count : 7

Visit Count : 45

Keywords

Work-Family Conflict; Job Satisfaction; Social Support; Female Nurses; Stress and Coping

How to cite this article

Aboagye, F., & Yamoah, E. E. (2025). Work-family conflict and job satisfaction among female nurses: The moderating role of social support in Ghana’s health sector. Management Issues in Healthcare System, 11, 37-53. https://doi.org/10.32038/mihs.2025.11.03

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interests

No, there are no conflicting interests.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/